In this piece, Dr Aveek Bhattacharya, Research Director at the Social Market Foundation, draws on economic theory and historical experience to explore the relationship between economic growth and inequality.

Is there a trade-off between raising economic growth and tackling inequality?

Stereotypically, parties of the right are supposed to be more focused on ‘growing the pie’ (increasing national income), whereas parties of the left are more preoccupied with dividing it up (reducing inequality). That assumption is not necessarily based in fact. Economic growth rates have been essentially the same in the past 50 years under governments of left and right. Inequality ballooned under Thatcher, flatlined under New Labour, and has fallen back a little since.

All the same, Keir Starmer’s government has been keen to shift the traditional perception, with Chancellor Rachel Reeves recently insisting that economic growth is its “number one mission”. That has led some to worry that Labour are taking their eye off the ball when it comes to addressing inequality and poverty – reflected for example, in the row over the government’s unwillingness to lift the two child benefit cap.

Is there a genuine tension or trade-off between these objectives, or can the government have its pie and eat it? That gets us into a set of questions economists have been probing for decades, helpfully reviewed in a 2019 paper by the LSE Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE).

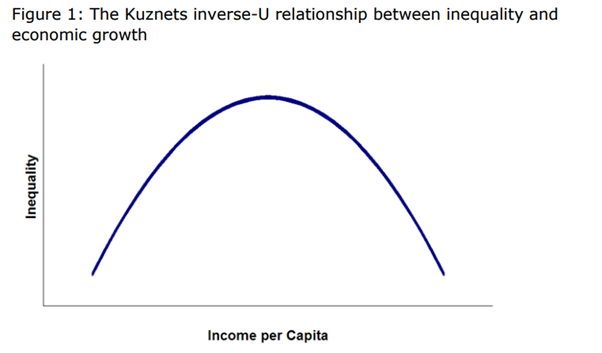

The standard starting point when discussing the relationship between economic growth and inequality is the ‘Kuznets curve’. Proposed by the economist Simon Kuznets (the man who literally invented GDP), this suggests that plotting income inequality against national income gives us an ‘inverse-u’ shape. When poor countries develop, inequality initially rises as a gap opens up between industrializing towns and poorer rural areas. Beyond a certain point, though, growth becomes more inclusive and inequality falls again. Yet while this pattern described Western countries reasonably well up to the 1970s, it failed to predict the subsequent rise in inequality along with growth in the late 20th Century, leading to what Branko Milanovic calls ‘Kuznets waves’: waxing and waning of inequality with growth. In his view, technological changes that create more productive jobs for better educated workers, buttressed by globalisation and policies that favour the rich have contributed to higher inequalities.

However, it isn’t clearcut whether we are on the upswing or the downswing of the Kuznets curve, and thus whether further growth will bring higher or lower inequality.

In any case, more attention has been paid to the reverse question: does inequality support or inhibit economic growth? On that issue, the classic concept bears the name of a different postwar economist: “Okun’s leaky bucket”. As Arthur Okun put it, “money must be carried from the rich to the poor in a leaky bucket. Some of it will simply disappear in transit, so the poor will not receive all the money that is taken from the rich”. Reducing inequality, on this view, weakens incentives for people to produce wealth and invest in the economy, which in turn means there is less to share. Policymakers who want to redistribute must decide how much economic growth they are willing to lose through the hole in the bucket for it still to be worthwhile. Indeed, a number of studies do show a positive correlation between income inequality and economic growth, as this theory would suggest.

On the other hand, there are reasons to worry that high inequality is bad for the economy. A society with more rich people with excess savings might be one with high investment, but equally that means low spending which would produce inadequate demand. That money could be channeled into unproductive status goods and commodities like housing, leading to asset bubbles. Poorer households could be driven to take on unsustainable debt, creating vulnerability in the financial system – it has been suggested that inequality drove the subprime lending before the global financial crisis. There are also studies that find rising inequality drags down growth.

Even by the uncertain standards of growth theory, the implications of this literature are opaque. As the CASE review puts it, “there is empirical evidence supporting both hypotheses. Results seem to hinge on data quality, differences in measures used, choice of control variables and statistical estimation techniques”. Their suggested way to reconcile the messy evidence is to say that “the relationship between inequality and growth is non-linear”. By that, they mean there is some evidence to suggest another ‘inverse-u’ exists: up to a certain level, higher inequality is good for growth, but if it gets too high it acts as a brake on the economy. That implies a ‘goldilocks’ level of inequality that is optimal, but we certainly cannot say with any confidence where it is.

Which is all rather unhelpful for judging the current government’s economic policy. Perhaps boosting social spending and mitigating poverty and inequality would be good for the economy, or possibly the taxes needed would go too far. Perhaps the rising tide of economic growth will lift all boats, or maybe it will drive the rich further away from everybody else. All we can say is there do not seem to be any inevitable relationships.

Perhaps the main lesson is that the government cannot just assume that growth will address inequality. It should also be wary of wishful thinking and carefully scrutinise claims that addressing poverty is an investment that brings a growth dividend, but it should be equally sceptical of those that assume redistribution is economically dangerous. As ever, details matter and evidence only takes us so far – the rest depends on judgement.

About the author

Dr Aveek Bhattacharya is Research Director of the Social Market Foundation, having joined as Chief Economist in September 2020. Prior to that, he was Senior Policy Analyst at the Institute of Alcohol Studies, researching and advocating for policies to reduce alcohol-related harm. He has also previously worked for OC&C Strategy Consultants, advising clients across a range of sectors including retail, consumer goods, software and services.

Aveek studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at undergraduate level, and has Master’s degrees in Politics (from the University of Oxford) and Social Policy Research (from the London School of Economics). He holds a PhD in Social Policy from the London School of Economics, where his thesis compared secondary school choice in England and Scotland. Aveek is co-editor of the book Political Philosophy in a Pandemic: Routes to a More Just Future.

Image credit: Tom Parsons on Unsplash